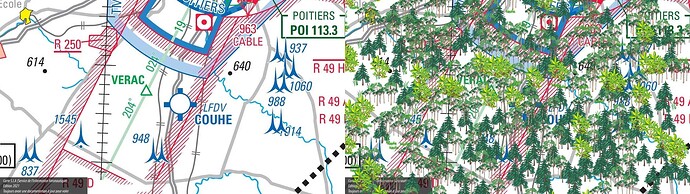

A map’s value lies in its ability to convey the essential information required to navigate a territory without omitting what matters, yet without being cluttered with unnecessary elements. A chart designed for commercial pilots would be useless if it marked every tree and streetlight, while a municipal electrician must know the exact position of each lamp, the type of bulbs used, and the network they connect to. Every purpose determines its own level of detail.

The same principle governs the world of mechanical pencils. Whether one is a consumer buying a pack of leads, an industrial engineer verifying their quality, each requires a different degree of precision. As one becomes more knowledgeable about mechanical pencils, it becomes fascinating to notice these shifting levels of abstraction.

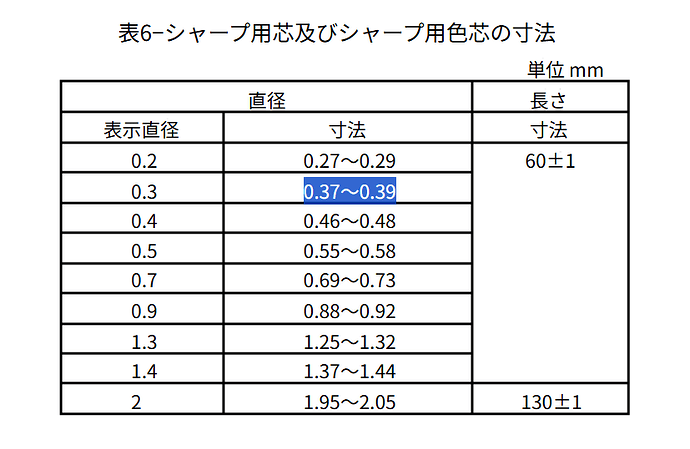

Consider the familiar 0.3 lead. The label is a convenience, not a statement of fact. In truth, those slender rods of graphite measure between 0.37 and 0.39 millimeters. Notably, the more design‑savvy brands now omit the “mm” on their packaging, as if to nod subtly to this truth.

The Japanese standard JIS S 6005:2019 defines these real dimensions and the simplification that consumers see. To the uninitiated, a 0.3 lead that is actually 0.38 mm in diameter may seem a rounding error. Yet anyone who understands how a clutch grips, how a sleeve guides, or how a feed advances the lead knows that this minute tolerance ensures every brand’s components fit together seamlessly. Because manufacturers adhere to the same standard, users can insert nearly any lead into any pencil and expect flawless performance.

This quiet coordination among companies keeps our mechanical pencils reliable and our writing uninterrupted. Departing from that shared ground offers no technical advantage. Major brands distinguish themselves instead through materials, design, and other refinements rather than redefining a standard that suits everybody.

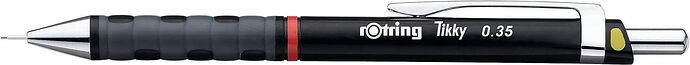

Even so, marketers often longs for exceptions. If one is cynical, one could describe the entire field of marketing as the task of presenting the ordinary as something exceptional. When rOtring introduced its so called 0.35 models, it was less a feat of engineering than an act of calculated defiance. A German rebellion against Japanese hegemony.

It disrupted an unspoken pact that prized interoperability over hype. In doing so, it introduced a confusing distinction that ordinary consumers could have done without. It sabotages the comfort of knowing that the next time you reach for a lead labeled 0.3, it will fit, even if the number tells only part of the truth.

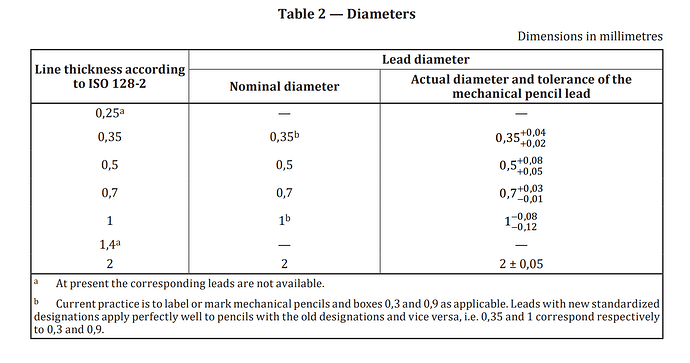

The story doesn’t end there. German manufacturers lobbied successfully to have their lead sizes incorporated first into ISO 9177-1 and later into ISO 9177-2. As a result, we now have two parallel labelling systems: the Japanese standard developed by Pentel and adopted by most brands, like Pilot and Uni, and the so-called international one—more European than genuinely global—championed by rOtring and Faber-Castell.

A kind of compromise was reached by admitting that the ISO standard merely restates what the JIS standard had always been, though with different labels and excluding the lead sizes not produced by German manufacturers. Since the 0.5 and 0.7 sizes share the same labels, and the 0.35 and 1.0 sizes are perfectly compatible with 0.3 and 0.9 leads, the latter can therefore be labelled accordingly in parentheses.

Now consumers are led to believe they must buy German leads to fit German 0.35 mechanical pencils, while the packaging ambiguously suggests that the same leads could also be used in 0.3 Japanese pencils, though perhaps not the other way around.

In reality, all leads, whether they follow the JIS or ISO naming convention, are functionally identical. A lead labelled 0.3 is the same size as one marked 0.35, and neither is actually 0.3 mm or 0.35 mm in diameter, but rather between 0.37 mm and 0.39 mm—that is, 0.38 ± 0.01 mm.

0.3 (JIS) = 0.35 (ISO) = 0.38±0.01 mm